Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition

Overview

-

What do Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition Refer To?

Enteral nutrition refers to any method of feeding that uses the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to deliver nutrition and calories. It can include a normal diet taken by mouth, the use of liquid supplements (such as protein shakes), or use of a feeding tube. The site of entry of the tube and tube types are discussed under "enteral access." Parenteral nutrition (often abbreviated TPN) refers to the delivery of calories and nutrients into a vein. This could be as simple as carbohydrate calories delivered as simple sugar in an intravenous solution or all the required nutrients could be delivered including carbohydrates, protein, fats, electrolytes (such as sodium and potassium), vitamins and trace elements (such as copper and zinc). There are many reasons a person may need enteral or parenteral nutrition including some GI disorders such as bowel obstruction, short bowel syndrome, and Crohn's disease; as well as certain cancers (such as those in the mouth, throat, or esophagus) or in patients with severe neurological damage which can occur after a stroke or brain injury. While enteral nutrition is always preferred, some people may have certain factors that make the safe use of the GI tract difficult. In this situation, their calorie and nutrient needs may not be met entirely by the GI tract, therefore parenteral nutrition may be needed to help an individual remain hydrated and to provide the calories and other nutrients to allow for maintenance of physical well-being and function.

Enteral Nutrition

- When Would a Patient Really Require Enteral Nutrition?

Enteral nutrition is needed when a person cannot meet their nutritional goals through a normal oral diet and their GI tract is working normally. It is important to use the GI tract for enteral nutrition because this type of nutrition is closer to normal and helps the immune and GI systems work. An example might be a patient who has had a stroke and now has difficulty swallowing (called dysphagia). This patient’s swallowing may or may not get better over time, but any improvement could take weeks to months. Given this, use of enteral nutrition would be recommended. Another example could be a patient with a newly diagnosed cancer in the throat who will need surgery. The surgery will make eating by mouth difficult so enteral nutrition will be needed to keep this person fed and nourished.

- What is Meant by and What are Examples of Enteral Access?

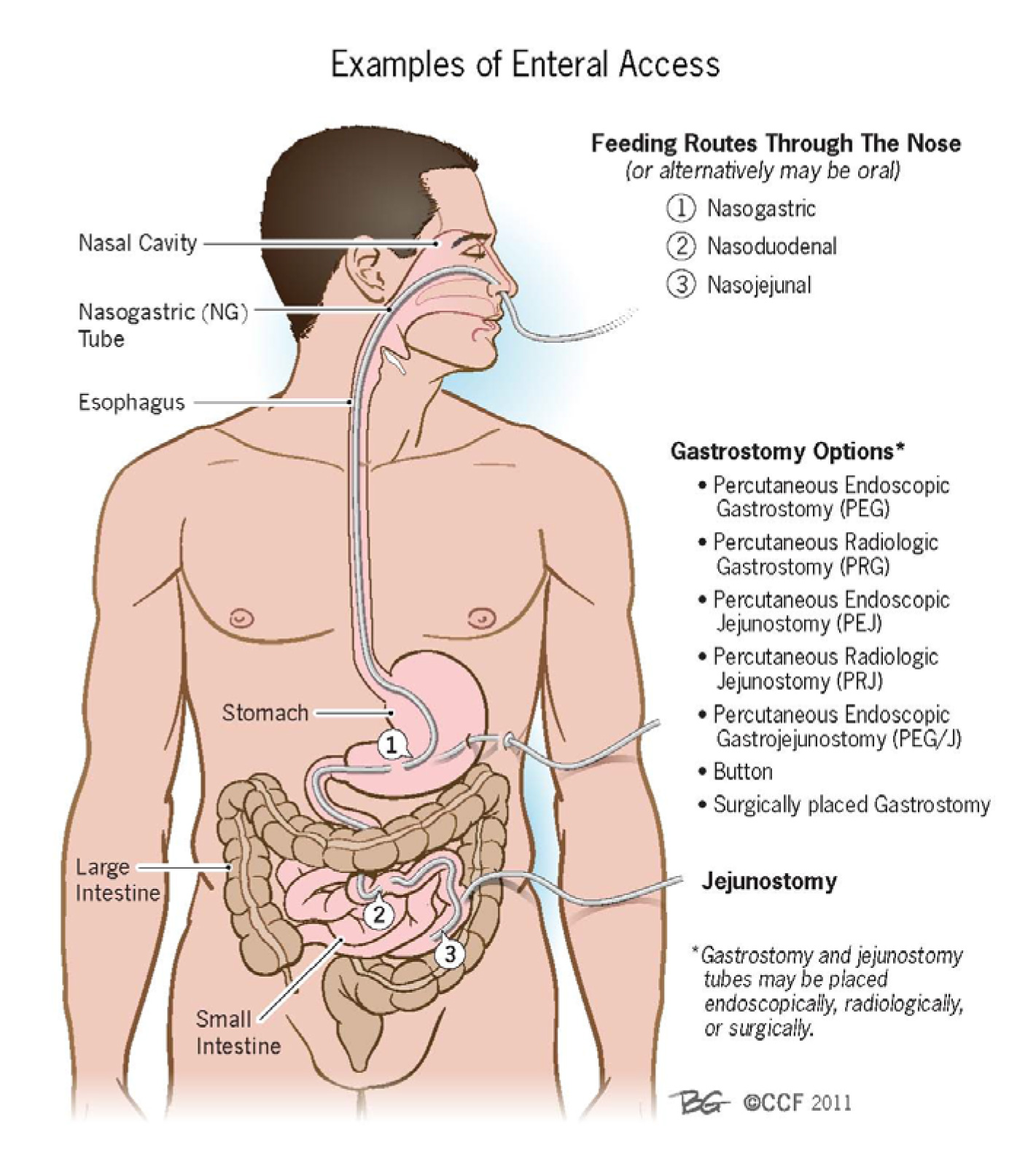

Enteral access refers to the way that the GI tract is accessed for enteral nutrition. Enteral access is most commonly via a tube, catheter, or a surgically made hole into the GI tract. When enteral nutrition is only needed for the short-term (4 weeks), patients will typically have a gastrostomy tube or jejunostomy tube placed. These types of tubes are most often placed by gastroenterologists during an upper endoscopy procedure and the tubes are often referred to as ‘PEGs’ when placed into the stomach or ‘PEJs’ when placed in the small intestine. These types of tubes can also be placed by interventional radiologists and by surgeons. The exact type of doctor that places the tube depends on multiple patient-specific factors. Figure 1 below shows the types of options for short-term and long-term enteral access and Table 1 summarizes so important information about each type of access. For more information on percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEGs), please see the ACG patient resource of the same name underGI Procedures.

Figure 1

Table 1

Enteral access device Length of use Pros Cons Nasogastric tube (NGT; through the nose) Short-term use Easy to place, variety of sizes available for patient comfort Not indicated if bleeding disorder, nasal/facial fractures and certain esophageal disorders Orogastric tube (through the mouth) Short-term use Lower incidence of sinusitis than NGTs Not tolerated for long periods of time in alert patients; tube may damage teeth Post-pyloric tube (generally thought of as a tube beyond the stomach) Short-term use Smaller diameter than NGTs and less patient discomfort; may be used in delayed gastric emptying May be difficult to position; smaller size tubes may make administration of some medications difficult, and an infusion pump is needed Gastrostomy tube (can be placed radiologically, endoscopically or surgically) Long-term use Easily cared for and replaceable; large size tube allows for bolus feeding, and administration of medications Compared with oral and nasal route, this technique is more invasive Jejunostomy tube (can be placed radiologically, endoscopically or surgically) Long-term use Decreases the risk of food and fluids passing into the lungs; allows for early postoperative feeding Technically more difficult to place; smaller size tubes may make administration of some medications more difficult, and an infusion pump is needed - What are the Complications of Enteral Nutrition?

Nutrition delivered by enteral tubes can cause the following complications: food entering the lungs (called aspiration), constipation, diarrhea, improper absorption of nutrients, nausea, vomiting, dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, high blood sugar, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, and decreased liver proteins. Feeding tubes inserted through the nose, such as nasogastric or nasoenteric tubes, can cause irritation of the nose or throat, acute sinus infections, and ulceration of the larynx or esophagus. Feeding tubes inserted through the skin of the abdominal wall, such as gastrostomy or jejunostomy tubes, can become clogged (occluded) or displaced, and wound infections can occur. It is important to note that complications from enteral nutrition are much less common than complications from parenteral nutrition (as summarized below).

- Can Enteral Nutrition be Done at Home?

Enteral nutrition is often done at home. Orders that specify details for administration and monitoring will be written by a provider or dietitian. Most protocols require the prescriber to indicate the formula for feeding, strength, how quickly to feed, and delivery method. Delivery methods include the following: gravity controlled and pump assisted. Gravity controlled feeding refers to any feeding method that uses manually controlled devices to deliver a feeding which is almost always a gastric feeding. This may include a continuous gravity feeding that is manually controlled with a feeding bag and a roller clamp to help control the rate; and intermittent gravity feeding where 200-300 mL are delivered over 30-60 minutes every 4-6 hours; and, a bolus feeding where a specific volume of feeding is infusing via bag or a syringe rapidly over several minutes, usually at a rate of about 60 mL/minute. Pump assisted feeding utilizes an electric pump device to more precisely control the rate of delivery in patients who are at a higher risk of inadvertently getting formula in their lungs, sensitive to volume, have delayed gastric emptying or are being fed into the small intestine. The choice of the delivery method for a particular person depends on the type of enteral access device as well as the person's individual needs. Water flushes should be administered to prevent clogging and ensure adequate hydration. Feeding tubes should be flushed with water before and after medication delivery and before and after every feeding or every 4 hours during continuous feeding. Often a dietitian, nurse or home care company will teach the patient how to prepare, administer, and monitor tube feeds. In addition, a home health care company may be available to explain the supply options available and help to arrange for home supplies and equipment.

Parenteral Nutrition

- Who May Benefit from Parenteral Nutrition?

Anyone who cannot eat or cannot maintain their fluid and/or nutritional status by eating by mouth or by tube feeding may be appropriate for intravenous nutrition. Again, the preferred route for nutrition is by using someone's GI tract through enteral nutrition, but this is not always possible. The intravenous route is more complicated, expensive, and always needs to be started in the hospital.

- What Are the Options for Delivering Parenteral Nutrition?

Parenteral nutrition is given by a central venous catheter device, which may include short term catheters which are tubes that are put in place in the hospital and generally removed prior to discharge and long term options (such as tunneled catheters) located in the upper chest, peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) located in the upper arm, and ports implanted under the skin usually in the upper chest wall. (See figures 2 and 3 below). Many catheters are available with multiple tubes (lumens) which allow for simultaneous infusion of fluids and/or medications. Central venous catheters are commonly used for patients requiring weeks, months or years of therapy. These are tunneled under the skin and most commonly placed by an interventional radiologist. They require dressing care to be performed by the patient, a family member or home health staff. A PICC is commonly used in patients who require therapy for a short duration, usually for several weeks to a few months. A PICC is typically placed in the hospital by a specialized team of nurses or an interventional radiologist. Similar to tunneled lines, PICCs require ongoing care. Ports are often used for patients requiring months to years of therapy and are commonly used where intermittent infusion therapy is needed such as cancer chemotherapy. Care of a port is needed only when the port is accessed. This is done by cleaning the skin before placing the special needle into the port and monitoring the port site closely. Ports allow people to maintain their body image, and there are no external components that may be prone to damage when the port is not in use. Placement of a port is typically done by an interventional radiologist.

Figure 2: Catheters - Parenteral Nutrition – Temporary

Figure 3: Catheters - Parenteral Nutrition – Long Term

- What Are the Complications of Parenteral Nutrition, and How Can They be Prevented or Decreased?

The most common complications associated with parenteral nutrition include infection, clogging (occlusion), and breakage. Infection can occur both at the site of the catheter (skin infection) or in the bloodstream (sepsis/bacteremia). A skin site infection is typically not serious and treated with a course of antibiotics. Bloodstream infection, called sepsis or bacteremia, can be a life-threatening complication of parenteral nutrition that typically requires hospitalization, IV antibiotics, and removal of the catheter. Very close and strict care of the catheter site can help to prevent infection. Catheter occlusion/clogging can occur due to improper care or as a side effect of parenteral nutrition. Catheters can often be de-clogged with medication, but sometimes cannot be and must be replaced. When a catheter is cracked, leaking, or broken, the catheter must be repaired or replaced as soon as possible.

Thrombosis (blood clot) of a blood vessel around an intravenous catheter is another potential complication with intravenous therapy as well as intravenous nutrition. Many factors play a part in the clotting of a vessel and different institutions may have special protocols for both prevention and treatment.

- Can Parenteral Nutrition be Done at Home?

Home parenteral nutrition (HPN) requires a team of clinicians to successfully manage and minimize the associated complications as discussed above. Home parenteral nutrition may be performed for many conditions as a short-term therapy or as a long-term therapy. As the parenteral nutrition formula is being adjusted in preparation for discharge from the hospital, the patient and caregiver will receive education on catheter care, operation of the infusion pump, parenteral nutrition set-up and disconnect procedures, maintenance of intake and output records, review of metabolic complications, and contact numbers for associated problems that may arise. All patients are monitored closely for electrolyte disturbances with routine blood draws to assure stability on HPN formula and clinic visits. If a patient needs readmission to the hospital, the nutrition support team and home nutritional support clinician will often work with the hospital team to provide continuity of care.

- Can I Work While on Parenteral Nutrition?

There are many individuals who continue to work and have very full and productive lives while receiving parenteral nutrition. The main determinant will be the degree of disease that caused the need for parenteral nutrition, as well as any symptoms the patient is experiencing. Each person needs to be assessed individually as to their wishes and overall medical condition to determine if they are well enough to work.

Authors and Publication Dates

Donald F. Kirby, MD, FACG, and Keely Parisian, MD, The Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH – Published September 2011.

Ryan K. Fawley, MD, Naval Medical Center, San Diego, CA – Updated April 2021.

Joshua L. Hudson, MD, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC – Updated April 2025.

Resources for More Information on Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition

Oley Foundation – The Oley Foundation is a national, independent, non-profit 501 (c) (3) organization that provides information and psycho-social support to consumers of home parenteral (IV) and enteral (tube-fed) nutrition (homePEN), helping them live fuller, richer lives. The Foundation also serves as a resource for consumers' families, homePEN clinicians and industry representatives, and other interested parties. – www.oley.org

ASPEN – American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition – ASPEN is a national organization composed of nutrition professionals including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, dietitians and members of industry who are dedicated to improve patient care by advancing the science and practice of clinical nutrition. – www.nutritioncare.org